Policy Briefs

Inflated Beyond Fiscal Capacity: The Need to Reform the Public Sector Wage Bill

Executive Summary

This policy brief addresses the issue of Yemen’s bloated public sector. Due to decades of corruption and patronage appointments, among other factors, public sector salaries were already a source of fiscal stress prior to the ongoing war. Previous efforts to downsize the public sector, notably those supported by the World Bank, produced few tangible results, as this brief outlines. During the conflict, the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the armed Houthi movement have added to the public sector payroll — particularly in the military and security apparatus — as the economy has contracted. Amid consistently large budget deficits, the inflated public sector wage bill is fiscally unsustainable and threatens to undermine economic recovery and future stability in Yemen.

This policy brief offers recommendations to reduce the public sector wage bill in Yemen, taking into consideration lessons learned from previous failures. Recognizing the multiple challenges of reforming the public sector, even in a stable country, these recommendations are addressed to the post-conflict government. It is recommended that the post-conflict government should: conduct an assessment to evaluate the conflict-driven growth of the public sector payroll; reduce administrative corruption through the biometric registration of all public sector workers; and develop a strategy to demobilize and reintegrate fighters into society without absorbing them into the public sector. It also recommends medium to long-term reforms to achieve a fiscally sustainable, efficient public sector, including an audit of public services, payroll reduction through attrition and the development of transparent hiring procedures.

Introduction

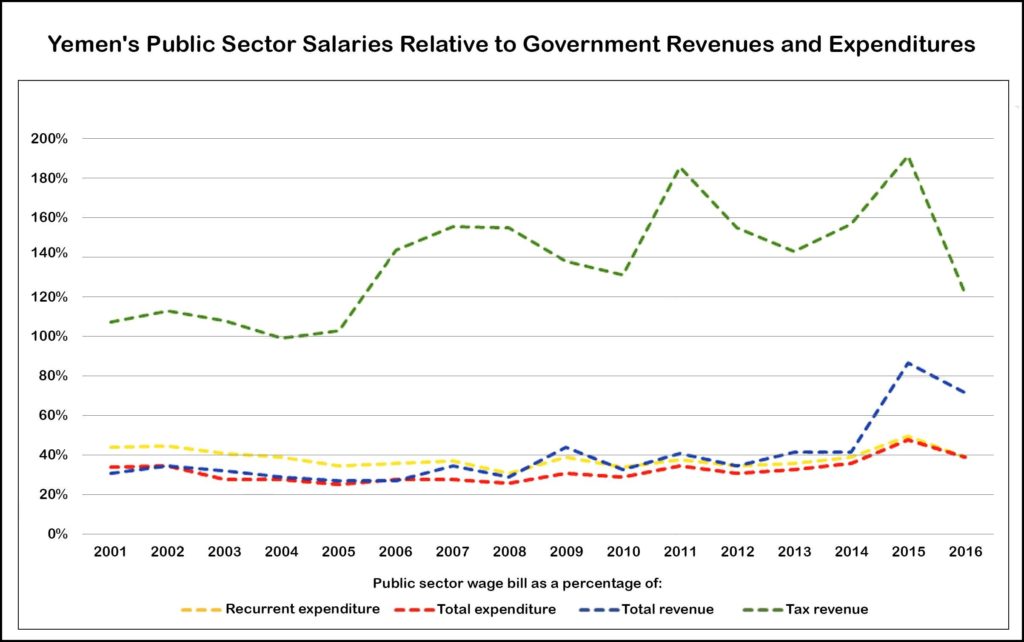

Yemen’s bloated public sector employment was a strain on the state budget prior to the conflict, accounting for an average of 32 percent of government spending between 2001 and 2014.[1] During the conflict, the warring parties have added large numbers of new employees to the public payroll, particularly the military and security services, while Yemen’s economy has shrunk.[2] Yemen is also struggling with a large public budget deficit, which was estimated at 660 billion Yemeni rials in 2018, equivalent to US$1.24 billion (at the average US$/YR exchange rate for 2018).[3] Post-conflict, reconstruction will be a priority for public expenditure and external support; Yemen may struggle to find consistent funding for public sector salaries.

Amid a liquidity crisis, the Central Bank of Yemen stopped distributing salaries in August 2016. Salary payments in some areas and sectors have since resumed, but full, regular payments to all public sector employees have not yet been achieved.[4] While resuming salary payments to civil servants is an urgent priority to help relieve the humanitarian crisis in Yemen, the inflation of the public sector is a looming crisis that must be addressed if Yemen is to achieve economic stability in the future. Post-conflict Yemen will also have to grapple with the reintegration of tens of thousands of fighters employed by the warring parties. It will not be fiscally viable to integrate them all into the state military and security bodies; however, other provisions for these fighters must be made in order to ensure they do not become spoilers to the peace process.

Background

The bloating of Yemen’s public sector is the cumulative outcome of several decades of mismanaged public sector employment policies as well as multiple forms of administrative corruption. In 1990, the unification of North Yemen and South Yemen led to the merging of two public sectors, both of which were swollen by state employment policies that did not take into account the actual needs of public institutions. Former President Ali Abdullah Saleh and his regime used public sector employment as a direct form of patronage throughout his 33 years in office, particularly within the military and security apparatus. Saleh’s regime’s use of public sector employment as a political tool continued to the end of his presidency; in 2011, the beleaguered president issued a decree to employ 60,000 university graduates and holders of post-secondary diplomas to try and stem the rising tide of opposition.[5]

Yemen’s public sector workforce has long included a high-number of ‘ghost workers’ – individuals that either do not report for duty or do not exist – and ‘double dippers’, who take multiple salaries from different public sector sources. Under Saleh, military and security leaders were given money and equipment according to the number of soldiers under their command, leading them to inflate the numbers of soldiers they commanded.[6] They would then receive extra salaries and equipment which could be sold on the black market or used for other purposes, such as bribery etc. After Saleh stood down as president in February 2012, various political actors within the transitional government headed by President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi looked to strengthen their support bases as they jockeyed for positions. One way to achieve this was by gifting public sector employment.[7]

After the armed Houthi movement (Ansar Allah), supported by forces loyal to Saleh, captured Sana’a in September 2014 and forced President Hadi into exile in March 2015, the Houthi authorities pursued their own targeted, public sector employment strategy.[8] This has included the replacement of long-serving public sector employees in Sana’a-based ministries (particularly the ministries of defense and interior) and other state institutions with handpicked Houthi supporters. The Houthi authorities have also appointed civilian, military, and security officials who are not on the official payroll.

Reintegrating Fighters Post-Conflict

As is the case with a number of armed groups that are active in the conflict, there are Houthi-affiliated fighters receiving salaries who are not registered. Added to this, a number of military and security officials within the movement’s ranks have been rapidly promoted. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of fighters have been integrated into the internationally recognized Yemeni government’s military and security apparatus, and military personnel have received their monthly salaries on a more regular basis than civilian public sector employees. Due to the lack of transparency and questionable payroll payment procedures, it is widely believed that military commanders continue to inflate the number of men under their command in order to receive salary payments for these ‘ghost soldiers’.[9] A major contributing factor on the Yemeni government side is the presence of two wealthy patrons, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). While Riyadh bankrolls the forces operating under the command of the Yemeni government, Abu Dhabi pays the salaries for the local security forces it helped establish that operate in Aden, Abyan, Shabwa and Hadramawt. Members of the UAE-backed Security Belt Forces in Aden are known to receive two salaries – one from the UAE and another from the Yemeni government.[10]

In the event of a peace deal, former fighters will need to be reintegrated into civilian life; if left armed and without salaries, they could become spoilers to the peace process. It will not be fiscally sustainable to absorb all fighters into the state military and security forces post-conflict. Thus, adequate support and incentives must be provided in the form of a national rehabilitation and reintegration program that incorporates fighters into the labor force. Fighters are driven by multiple factors, including unemployment, economic malaise and despair, as well as ideological beliefs; while fighters should not be integrated en masse into the public sector, bringing them into the workforce will be critical to the long-term stability of Yemen, and the wider region.

Current Assessments of Yemen’s Public Wage Bill

Public sector salaries in Chapter 1 of the internationally recognized Yemeni government’s budget for 2019 account for 39.33 percent of projected expenditure. Salaries for some state funds and independent units are not included in Chapter 1 of the budget, so this figure does not reflect full government wage expenditure. [11]

Figure (1): Government spending on Chapter 1 public sector wages (millions, Yemeni rials)*

| Item | Military & Security | Civilian | Total Cost |

| 2014 Budget | 430,212 | 546,873 | 977,085 |

| 2018 Expenditure | 558,181 | 271,064 | 829,245** |

| 2019 Budget | 528,629 | 694,896 | 1,223,525 |

Source: Ministry of Finance, Government of Yemen

*All figures are rounded to the nearest million.

** This figure is lower than 2014 because the Yemeni government only paid salaries to 51 percent of civil service employees in 2018.

The projected expenditure for 2019 does not, however, include those in military and security units in Houthi-controlled areas, nor those appointed by the Houthi authorities during the conflict. Houthi authorities have appointed staff to ministries in Sana’a and to institutions they control, including the Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) and the Red Sea Ports Corporation. The Houthi authorities have also created new bodies, such as the National Authority for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Recovery (NAMCHA) that oversees coordination among different humanitarian organizations and aid programs. A number of people are also employed by the Houthis in informal positions or in quasi-state institutions, such as those operating under the umbrella of the Supreme Revolutionary Committee and the Houthi-appointed supervisors or “mushrifs” as they are referred to locally. While accurate statistics on the current number of public sector employees in Yemen are not available, it is clear that the size of the payroll has grown since 2014, when it stood at 1.25 million.

Failed Efforts to Reform the Public Sector

Previous costly efforts to implement reforms and address the corruption that has inflated Yemen’s public sector wage bill have failed to produce tangible results. In the early years of the new republic, the Yemeni government used salary cuts to try and reduce its wage bill, which had increased with the merging of two public sectors after unification in 1990. By 1996, average real wages for public sector staff had been cut to 15 percent of their 1990 levels, and senior managers earned just 11 percent of the salaries of their private sector peers.[12] These low wages encouraged absenteeism and low productivity, as well as practices like double dipping, ghost workers and corruption.

In 1998, the Yemeni government adopted the Strategic Framework for Civil Service Modernization to restructure public employment, establish a transparent personnel management system and reduce the number of redundant workers, among other aims. The World Bank supported the government’s reform agenda with a range of financing mechanisms, including a flagship US$30 million project approved in April 2000 to put in place personnel and financial management systems, remove 34,000 redundant employees and remove all double dippers and ghost workers from public employment, among other objectives.

A decade later, the Civil Service Modernization Project had identified 17,753 redundant employees, mostly from defunct state enterprises. In addition, 3,792 double dippers had been removed from the payroll, of whom 3,767 had come forward voluntarily while just 25 were identified through databases developed by the project.[13] No ghost workers had been identified. The project also aimed to streamline organisational structures in ministries, but there was little evidence of implementation or results in this area, according to the World Bank’s evaluation. Overall, the project failed to reduce the number of civil servants or the size of the wage bill, which doubled from 281 billion Yemeni rials in 2005 to 597 billion Yemeni rials in 2010.[14]

The World Bank’s internal evaluation concluded that the project was overambitious in scope and sophistication, and underestimated the sensitivity and inherent political nature of the reforms, as well as the welfare, cohesion and patronage functions of the public sector in Yemen.[15] The attempted reforms were also hindered by weak inter-ministerial coordination; an absence of government commitment to reform; poor donor coordination; an unstable political and security situation, which affected the government’s authority and capacity to push reforms in some areas; weak governance, including continuing corruption and patronage; pressure from regional and tribal constituencies that relied on public sector employment in the absence of a strong labor market; and resistance to the establishment of a central civil service database and management systems in some decentralized governorates.

Law no. 43 of 2005 introduced a requirement to establish a civil service biometric fingerprint system and a central database of employees at the Ministry of Civil Service. However, this process was hampered by hardware and software limitations and, later, damage to technical infrastructure during the 2011 uprising.[16] The computer equipment and software only had the capacity to register 500,000 state employees, and there was insufficient budget allocated to upgrade the biometric system.[17] As the system was not linked to time and attendance software, it could not be used to identify ghost workers. Additionally, it was not integrated with payroll databases.[18] In 2013, the Yemeni government announced that it would implement a new program to remove ghost workers and double dippers from the civil, military and security services, supported by the UN Development Program.[19] The plans included restoring the databases, as well as upgrading the storage capacity of the database so all government employees could be registered. Yet, until now, biometric information that has been collected remains as raw data, and the databases that have been created only have the capacity to identify duplicate names.

Recommendations

Addressing a bloated public sector is a significant and demanding undertaking that requires sustained political will, public buy-in and adequate institutional capacity and resources, even in a stable country. For a country at war, reforms may face insurmountable challenges and thus the following recommendations are focused on a post-conflict scenario. These recommendations take lessons learned into account and advocate for a phased, gradual approach to each step.

Near-Term Priorities in a Post-Conflict Scenario

- Evaluate the size of the public sector:

- An independent civil service commission should be established, as recommended by the National Dialogue Conference, to administer the civil service. Among its first tasks should be to begin an evaluation of the number of people on the civil service payroll. This body should also be responsible for instituting fair hiring practices in the civil service, determining employment conditions and developing job descriptions for all civil service roles.

- An assessment should also begin of the number of people on the payroll of military and security institutions, which have experienced the most growth since the start of the conflict. This could be performed by an independent committee, and would initially require the ministries of defense and interior and military public institutions to disclose records of all employees.

- Evaluations of the size of the public sector should reflect all those added to the wage bill by the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the armed Houthi movement during the conflict, as well as staff turnover since 2014.

- Reduce administrative corruption: Political leaders and government institutions should undertake efforts to reduce the public sector wage bill by taking steps to remove double dippers and ghost workers from the payroll.

- Investments should be allocated to install the infrastructure and technical capacity needed to make the biometric system fully operational, to conduct biometric registration of all public sector employees, and to link the biometric data to the national database of national identification numbers. This would enable the government to identify and remove double dippers. By linking this national database to all state institutions’ records as well as time and attendance software, the government could also identify and remove ghost workers. Regulations should be developed to prevent and/or punish misuse or manipulation of data.

- The number of employees who are paid salaries via bank accounts should be increased, reducing the capacity for fraud.

- Demobilize and reintegrate former fighters: Political leaders and government institutions should develop a strategy to reintegrate fighters post-conflict as part of the political agreement to end the conflict. This strategy could be informed by successful reintegrations of fighters in other post-conflict contexts.

- A National Committee of Rehabilitation and Reintegration of Fighters should be established with representatives of the ministries of civil service, finance, defense, interior, and technical education and vocational training to implement a demobilization and reintegration program. It should be tasked with registering fighters, managing transitional funds to support disarmed fighters, and collecting weapons from former fighters.

- Attempts to reintegrate former fighters by expanding the public sector should be avoided. Options to incorporate former fighters into the labor force could include matching former fighters to jobs in the post-conflict reconstruction and recovery efforts, and vocational training matched to labor market needs.

Medium- to Long-Term Priorities

- Initiate gradual, sequenced reforms to achieve a fiscally sustainable, efficient public sector.

- The post-conflict government should identify crucial public services for auditing to identify appropriate staffing levels and increase the efficiency of service delivery; reduce the payroll through attrition, by not hiring replacements for staff who retire; and develop transparent hiring procedures and codes of conduct as initial steps toward instituting a merit-based selection process.

- Corruption should be minimized by: establishing legal penalties for unlawful hiring practices and developing mechanisms and procedures to implement these penalties; forming an independent oversight body to monitor hiring practices and improve accountability; and reviewing remuneration policies to ensure that government employees are fairly compensated, reducing the incentive for employees to commit fraud through double dipping and ensuring that qualified candidates are incentivized to join the public sector.

- The post-conflict government should also issue all citizens with a unique national number, from birth, to be electronically assigned by the civil registry and used in all interactions with government institutions, including public sector employment. As well as laying the ground for e-government, this would contribute to reducing capacity for double-dipping and ghost workers.

- Strengthen the private sector to create greater alternatives to public sector employment.

- Efforts to diversify the economy, improve the business environment, support the private sector, and promote vocational education will be vital to mitigating the impact of public sector reforms (For more details, see previous RYE Policy Briefs: Generating New Employment Opportunities in Yemen and Private Sector Engagement in Post-Conflict Yemen).

- Increase citizen awareness.

- Governing authorities, media and civil society should coordinate to develop communications campaigns to raise public awareness that an inflated public sector diverts public funds away from needed development and is a source of corruption. This could be a first step toward creating popular buy-in for reforms.

footnotes

[1] In 2014, public sector salaries cost the government 1.14 trillion Yemeni rials, which at the time was equivalent to $5,3 billion. See: Mansour Ali Al Bashiri, “Economic Confidence-Building Measures — Civil Servant Salaries,” Rethinking Yemen’s Economy, March 18, 2019, https://devchampions.org/publications/policy-brief/civil-servant-salaries.

[2] The World Bank estimated in April 2019 that Yemen’s GDP had contracted by an accumulated 39 percent since the end of 2014. See: “Yemen’s Economic Update,” World Bank, April 2019, http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/365711553672401737/Yemen-MEU-April-2019-Eng.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2019.

[3] “Starvation, Diplomacy and Ruthless Friends: The Yemen Annual Review 2018,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, January 22, 2019, http://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/6808#ED-macro. Accessed June 20, 2019.

[4] “Economic Confidence Building Measures - Civil Servant Salaries,” Rethinking Yemen’s Economy, March 18, 2019, https://devchampions.org/publications/policy-brief/civil-servant-salaries. Accessed July 23, 2019.

[5] Farea Al-Muslimi and Mansour Rageh, “Yemen’s economic collapse and impending famine: The necessary immediate steps to avoid worst-case scenarios,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 2015, http://sanaacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/files_yemens_economic_collapse_and_impending_famine_en.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2019.

[6] “Beyond the Business as Usual Approach: Combating Corruption in Yemen,” Rethinking Yemen’s Economy, November 2018, http://sanaacenter.org/files/Rethinking_Yemens_Economy_No4_En.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2019.

[7] Peter Salisbury, “Corruption in Yemen: Maintaining the Status Quo?” in Rebuilding Yemen: Political, Economic, and Social Challengers, ed. Noel Brehony and Saud al-Sarhan (Berlin: Gerlach Press, 2015)

[8] “Beyond the Business as Usual Approach: Combating Corruption in Yemen,” Rethinking Yemen’s Economy, November 2018, http://sanaacenter.org/files/Rethinking_Yemens_Economy_No4_En.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2019.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Although members of the UAE-backed Security Belt Forces in Aden operate under the direct control of the UAE, they are formally registered with the Government of Yemen’s Ministry of Interior, and thus receive a monthly salary from both the UAE and the government.

[11] Chapter 1, 2019 Budget for Government of Yemen

[12] “Implementation completion and results report on a credit in the amount of SDR 22.4 million to the Republic of Yemen for a civil service modernisation project,” The World Bank, December 2010, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/206391468340752501/text/ICR16880P050701OFFICIAL0USE0ONLY191.txt. Accessed June 20, 2019.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Action Plan to Implement the Program to Remove Ghost Workers and Double Dippers in the Civil Service System, Including the Military and Security,” Government of Yemen, https://www.undp.org/content/dam/yemen/DemDov/Docs/UNDP-YEM-biometric_en_Final.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2019.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.