Policy Briefs

An Institutional Framework for Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Yemen

Executive Summary

Previous reconstruction efforts in Yemen following conflict or natural disaster have suffered from lack of coordination with and unrealistic expectations from international donors, as well as the Yemeni government’s limited capacity for aid absorption and project implementation; as a result, there was little tangible long-term impact.

In light of lessons learned from similar post-conflict contexts and Yemen’s own history of reconstruction efforts, this policy brief proposes an institutional structure for a future reconstruction process in Yemen: a permanent, independent, public reconstruction authority that empowers and coordinates the work of local reconstruction offices, established at the local level in areas affected by conflict or natural disasters. This proposal does not arise only from these lessons learned, but also from the immediate need for such an institution to begin planning and implementing reconstruction work to the greatest extent possible.

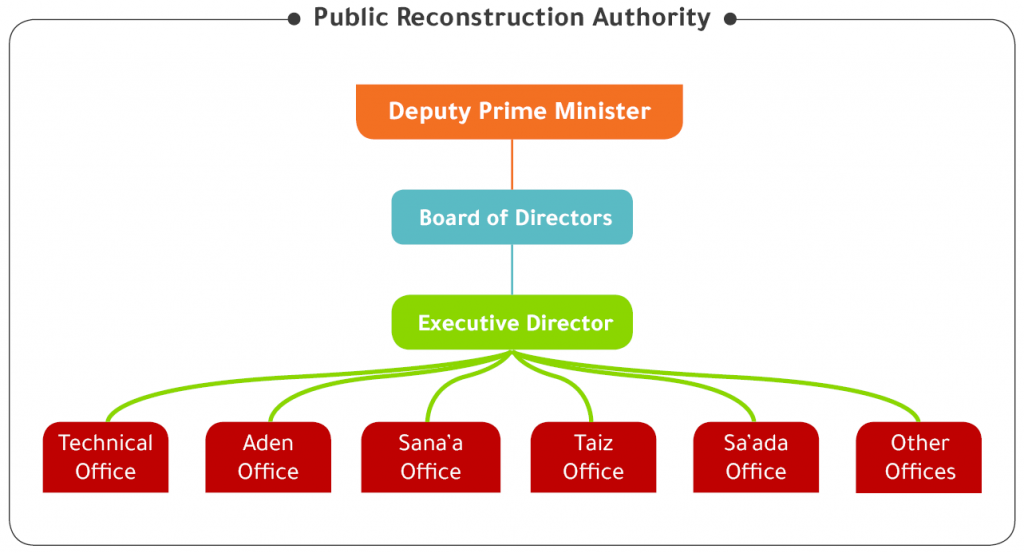

This reconstruction authority should have a clear mandate to manage all tasks required in reconstruction following the current conflict, but also future crises. Its board of directors should include a range of stakeholders and should be chaired by a deputy prime minister for reconstruction to ensure it has the highest level of support. It should take an inclusive, multi-level, mixed institutional approach, have a clear long-term plan for building state capacity, and establish its own monitoring and evaluation unit to demonstrate a commitment to transparency. Most importantly, it should establish a clear framework for working closely with all stakeholders.

Introduction

The current conflict in Yemen follows decades of political and economic turmoil. Any future reconstruction efforts will face a daunting task. For example, World Bank estimates from 10 cities in Yemen revealed a quarter of the road network was partially or fully destroyed as of 2016, with power production halved and half of all water, sewage and sanitation infrastructure damaged. With the intensification of the conflict since, it is expected that current levels of destruction are far greater.

In early 2017 the United Nations also declared Yemen the site of the world’s worst humanitarian crisis; as of April 2018, roughly 22.2 million Yemenis were in need of humanitarian assistance, including 8.4 million at risk of starvation. The country’s gross domestic product declined an estimated 47.1 percent from 2015 to 2017, while 40 percent of households have reported the loss of their primary income source. Most public services have been suspended, leaving 16 million people without access to safe water and 16.4 million with limited or no access to healthcare.

There is little sign of the conflict ending soon. Nevertheless, stakeholders concerned with establishing lasting peace in Yemen must urgently begin laying the groundwork for a comprehensive reconstruction framework to implement in the eventual aftermath of fighting. Experience has shown that it is never too early to begin planning for reconstruction.

This policy brief, which is based off of a more extensive White Paper, consists of the following sections:

- The first section provides an account of Yemen’s own history of post-crisis recovery efforts.

- The second section proposes a new institutional model for reconstruction: an independent reconstruction authority that establishes transparent mechanisms for coordination and accountability among all stakeholders.

The policy brief seeks to identify how to ensure the proper flow of funds and the timely completion and overall quality of post-war reconstruction projects. Beyond this, however, it emphasizes the importance of national ownership – meaning the inclusion and buy-in of all Yemeni stakeholders. Such an inclusive framework builds Yemen’s capacity to meet the basic needs and rights of its own people, thereby putting the country on the path toward lasting recovery.

Past Reconstruction Efforts in Yemen

Yemen has had numerous experiences with reconstruction efforts, given its decades-long history of poverty, natural disasters, and conflict. In recent decades, several natural disasters have hit Yemen. The 1982 earthquake in Dhamar killed up to an estimated 2,500 people and injured a further 1,500, with US$2 billion in losses. Although the independent Executive Office for Reconstruction, created following the earthquake, delivered thousands of earthquake-reinforced housing units, most of these remain uninhabited even today, due to their cultural unsuitability. The reconstruction office was also ineffective due to a limited capacity for coordination or monitoring. The 2008 flood in Hadramawt and al-Mahra caused an estimated US$1.6 billion in damage. The Hadramawt and al-Mahra Reconstruction Fund succeeded in engaging local stakeholders. However, it lacked any coordination mechanism or monitoring framework. Despite having resources, it lacked effectiveness: it struggled to utilize the US$210 million it was allocated, spending only 70 percent of its total available funding.

Yemen has also seen years of chronic unrest. Recurring conflict in Sa’ada governorate from 2004-2010 killed hundreds and wounded thousands more, while causing an estimated US$600 million in damages. The Sa’ada Reconstruction Fund had a US$55 million budget allocated from the Yemeni government. The fund neglected public infrastructure at the expense of rebuilding private properties and faced widespread accusations of “reconstruction bias,” directing rebuilding efforts to areas based on personal affiliations rather than need. The occupation of Abyan governorate by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and associated fighting in 2011-2012 left damage estimated at US$580 million. The Abyan Reconstruction Fund was allocated US$46.5 million. It did little to absorb this funding and quickly developed a reputation for mismanagement, corruption, and embezzlement. The fund’s evaluation report estimated US$4.2 million of fraudulent costs and a further US$1.4 million reported as compensation for ‘ghost’ beneficiaries.

At the demand of international donors, and following 2011 protests against then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh, the Yemeni government established the Executive Bureau in 2012 to build state capacity. However, it did not have the political power necessary to overcome resistance from ministries who viewed it as competition. When Houthi fighters seized Sana’a in late 2014, the Executive Bureau’s ability to function was further curtailed. Despite later attempts to revive it, the Bureau’s World Bank funding expired in mid-2015; as the security situation deteriorated, funding for the Bureau was withdrawn.

Yemen also has examples of innovative initiatives for delivering public services, though not in a post-conflict context. Since the mid-1990s, semi-autonomous agencies have operated parallel to the central government to deliver public services in rural areas. The Public Works Project, the Social Welfare Fund, and the Social Fund for Development provide models for effective, efficient, and transparent services provision in Yemen. They have a carefully designed legal mandate that provides sufficient autonomy while having a well-defined relationship with the government. However, they are designed to be only short-term alternatives; there is no clear strategy for how they might be permanently integrated into the government.

The Way Forward for Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Yemen

As mentioned above, previous Yemeni reconstruction efforts have shown an inability to absorb aid or to implement projects effectively. Past reconstruction initiatives thus do not provide a successful model for future reconstruction, particularly given that the current war’s destructiveness far outstrips that of past disasters or conflicts. However, there is the potential to build on the existing institutional blueprint of the Executive Bureau and, similarly, to initiate reconstruction interventions through local models that already have community buy-in, national reach, and a professional workforce: the Social Fund for Development, the Public Work Projects, and the Social Welfare Fund.

This paper proposes a way forward for reconstruction in Yemen through creating a proactive institutional framework to deal with the aftermath of the current war as well as future crises. This requires the establishment of a permanent independent Public Reconstruction Authority (PRA) operating to empower and coordinate the work of local reconstruction offices, created at the local level in areas affected by the conflict or natural disasters.

The mandate of the authority should be to manage all the tasks required in reconstruction: current and future post-conflict or disaster reconstruction planning; policy design; funding and fundraising; and coordinating with all stakeholders. The mandate should also include the tasks required for a transparent process: monitoring and evaluation; reporting; and overseeing strategic national projects.

To fulfill this mandate, the reconstruction authority should:

- Be a public, independent authority.

- Be established by a presidential decree that specifies its mission, authority, and responsibilities. It should have its own protocols for procurement, personnel, and payroll.

- Have a board of directors that includes a range of stakeholders: representatives from the donor community (both from within the Gulf Cooperation Council and from among international donors); representatives from the cabinet; and representation from the private sector, in addition to the executive director of the reconstruction authority. The board should be chaired by a deputy prime minister to ensure it has the highest level of support. The responsibilities of the board should be clearly and strictly limited to strategic-level direction, ensuring that the executive management of the reconstruction authority has the flexibility to implement reconstruction plans effectively.

- Set up local reconstruction offices that act as hubs to manage operations at the local level. The public authority will delegate power to these reconstruction offices, which are proposed to be established in Aden, Sana’a, Sa’ada and Taiz. These decentralized local offices will be mandated with the overall design and planning of the reconstruction effort at the local level. The authority should also be able, in the event of a crisis, to create additional local offices in other areas affected by conflict or natural disaster.

- Follow a competitive, merit-based, transparent process for the recruitment of its executive director and all staff. The reconstruction authority’s board (upon nomination of the executive director following the same competitive, merit-based, and transparent process) should appoint the directors of local offices. The same recruitment process should be followed to staff of local offices to deliver efficient and rapid reconstruction work.

- Adopt a mixed institutional approach. Any reconstruction framework must include key Yemeni stakeholders: the national government, local NGOs, the private sector, and arm’s-length government institutions such as the Social Fund for Development (SFD), the Public Works Project and others. Because it is impractical to rely solely on a weakened central government for immediate post-conflict reconstruction throughout all of Yemen, the central government should only be involved in strategic planning. In the immediate post-conflict years, the focus must be to implement small projects primarily in affected communities but also across all of Yemen. Focusing on the needs of affected areas need not mean ignoring the rest of the country – particularly if perceived favoritism leads to anger against the state. Efforts should further be devoted to the needs and development of women, youth, and marginalized groups.

- Establish a pool fund for all donors. This fund can be co-managed by the reconstruction authority and an international or regional development bank acting as a trustee. Such a fund could have a separate account, independent of the government budget, for the collection and disbursement of donor funds. This account should be held in a commercial bank approved by the reconstruction authority board; it should also be routinely audited by an independent organization according to the international auditing standards.

- Establish its own monitoring and evaluation unit. This unit can operate in conjunction with the monitoring and evaluation entities that already exist in the Yemeni government, such as the Central Organization for Control and Auditing; the Supreme National Authority for Combating Corruption; and the Supreme Judicial Council. In creating its own monitoring and evaluation unit, the reconstruction authority declares its aim to be accountable and transparent while maintaining a degree of national ownership over reconstruction.

- Develop a long-term strategic plan to restore, consolidate, and prioritize reconstruction funding from Yemeni sources. External funding can be expected to be ample in the short term, but may decline in the medium to long term. Such policies will ensure sufficient funds for long-term reconstruction efforts as external funding declines.

To manage relations with stakeholders, the reconstruction authority should:

- Coordinate closely with the Yemeni government at all levels. Each level of government should have a clearly specified scope of involvement: local authorities should work in collaboration with local offices and be able to propose projects, while the public reconstruction authority should work with the central government on national-level strategic planning. The cabinet should provide the Yemeni government’s share of funding and in-kind contributions. The line ministries should continue to deliver ongoing public services, submit data related to planned projects, and sustainably manage completed reconstruction projects. In turn, the reconstruction authority should provide the central government with technical advice, ensuring the government’s ability to maintain and sustain completed projects. Relations between local reconstruction offices and local authorities should follow the same pattern.

- Demonstrate to international partners a commitment to transparency and efficacy. Having donor representatives on the board of the reconstruction authority signals a true partnership between Yemen and the donor community. A formal compact can be signed between the government and international donors with the following aims: to clarify the roles of international partners; to identify a mechanism for compliance; to encourage donors to deliver funding over both short and long-term horizons; to outline government commitments, and ensure the national ownership of the reconstruction program.

- Include the private sector in the reconstruction process: private actors can fund, supply, and implement reconstruction efforts. The reconstruction authority should build capacity for strong public-private partnerships, issue competitive bids for projects, and source locally as much as possible for procurement needs.

- Treat local non-governmental organizations and local communities as important partners in reconstruction. No one knows better a local community’s needs than the members of the community itself; they have expertise in what works best in their community. These communities can offer an important channel for information on the reconstruction progress. NGOs may provide an important link to social groups particularly affected by the conflict, bringing the needs and concerns of those groups into the reconstruction process and monitoring the implementation of reconstruction projects. They may also facilitate consultations with local communities, women, youth, and marginalized groups. Meanwhile, universities, think tanks, consultancies, and business associations can provide a source of independent professional proposals, evaluations, and advice.

Reconstruction in Yemen must follow a model that responds to the realities on the ground, builds state capacity, ensures transparency, and coordinates efficiently. It must foster trust not only among donors but among Yemeni political actors and citizens at large. It must coordinate well with international donors while maintaining Yemeni ownership of reconstruction. Focusing efforts not only on affected areas but the Yemeni population as a whole will provide basic services and create job opportunities across regions. People are less likely to return to conflict if they are constructively occupied, earn an income and can plan for the future. They are also more likely to support the peace process if they experience increased well-being, see an improvement in public services, and hear of successful development projects. As such, an institutional model for reconstruction that emphasizes national ownership, transparency, and inclusiveness will have the best chance to consolidate peace in the long term.